Fainting on an empty stomach is more common than most people realize. While the medical term for fainting is syncope, the phenomenon of passing out due to low blood sugar or dehydration often goes underreported. Understanding the causes, symptoms, and preventive measures can help individuals avoid potentially dangerous situations. This article explores the latest guidelines and expert recommendations on managing and preventing fasting-related syncope.

The Physiology Behind Fainting

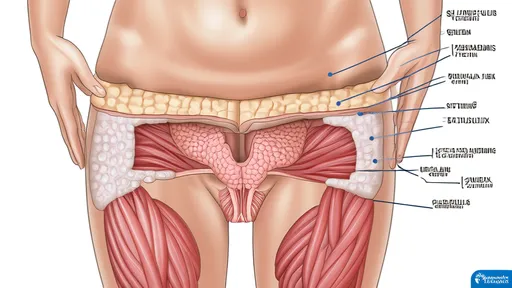

When the body is deprived of food for an extended period, blood glucose levels drop, leading to a condition known as hypoglycemia. The brain relies almost exclusively on glucose for energy, and when levels fall too low, cognitive function becomes impaired. This can result in dizziness, confusion, and ultimately loss of consciousness. Additionally, dehydration exacerbates the problem by reducing blood volume, further lowering blood pressure and compromising circulation to the brain.

Fasting-induced syncope often occurs in individuals who skip meals, follow restrictive diets, or have underlying metabolic conditions. Athletes, diabetics, and those with a history of vasovagal syncope are particularly susceptible. Recognizing early warning signs such as lightheadedness, sweating, or blurred vision can provide a critical window to intervene before a full blackout occurs.

Who Is at Risk?

Certain populations face a higher likelihood of experiencing fasting-related fainting episodes. Young adults, especially women, are disproportionately affected due to hormonal fluctuations and a tendency toward irregular eating habits. Individuals with eating disorders, such as anorexia or bulimia, are also at elevated risk because of prolonged malnutrition and electrolyte imbalances.

Elderly individuals may not always associate their symptoms with fasting, as age-related changes in metabolism can mask the signs of hypoglycemia. Diabetics, particularly those on insulin therapy, must be especially cautious, as their bodies may not regulate blood sugar efficiently during periods of fasting. Even healthy individuals engaging in intermittent fasting should be aware of their limits and avoid pushing themselves too far without proper hydration and nutrition.

Preventive Strategies

Preventing fasting-related syncope begins with maintaining stable blood sugar levels. Eating small, balanced meals throughout the day is more effective than consuming large, infrequent meals. Complex carbohydrates, lean proteins, and healthy fats provide sustained energy and prevent rapid glucose fluctuations. Hydration is equally important—drinking water consistently, especially in hot climates or during physical activity, helps maintain blood volume and circulation.

For those who must fast for medical or religious reasons, gradual preparation is key. Reducing caffeine and sugar intake in the days leading up to a fast can minimize withdrawal symptoms and blood sugar crashes. During the fasting period, avoiding sudden movements—such as standing up quickly—can prevent orthostatic hypotension, a common trigger for fainting.

When to Seek Medical Attention

While most cases of fasting-related fainting are benign, recurrent episodes warrant medical evaluation. Underlying conditions such as heart arrhythmias, adrenal insufficiency, or autonomic dysfunction could be contributing factors. A healthcare provider may recommend blood tests, cardiac monitoring, or a tilt-table test to rule out serious causes.

If someone faints, laying them flat with their legs elevated can help restore blood flow to the brain. Once conscious, they should consume a fast-acting carbohydrate like fruit juice or glucose tablets, followed by a protein-rich snack to stabilize blood sugar. Persistent confusion, chest pain, or difficulty regaining consciousness are red flags that require immediate emergency care.

Final Thoughts

Fainting due to an empty stomach is preventable with awareness and proactive measures. By understanding the physiological mechanisms and recognizing personal risk factors, individuals can take steps to avoid syncope. Whether adjusting dietary habits, staying hydrated, or seeking medical advice for recurring episodes, small changes can make a significant difference in overall well-being.

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025